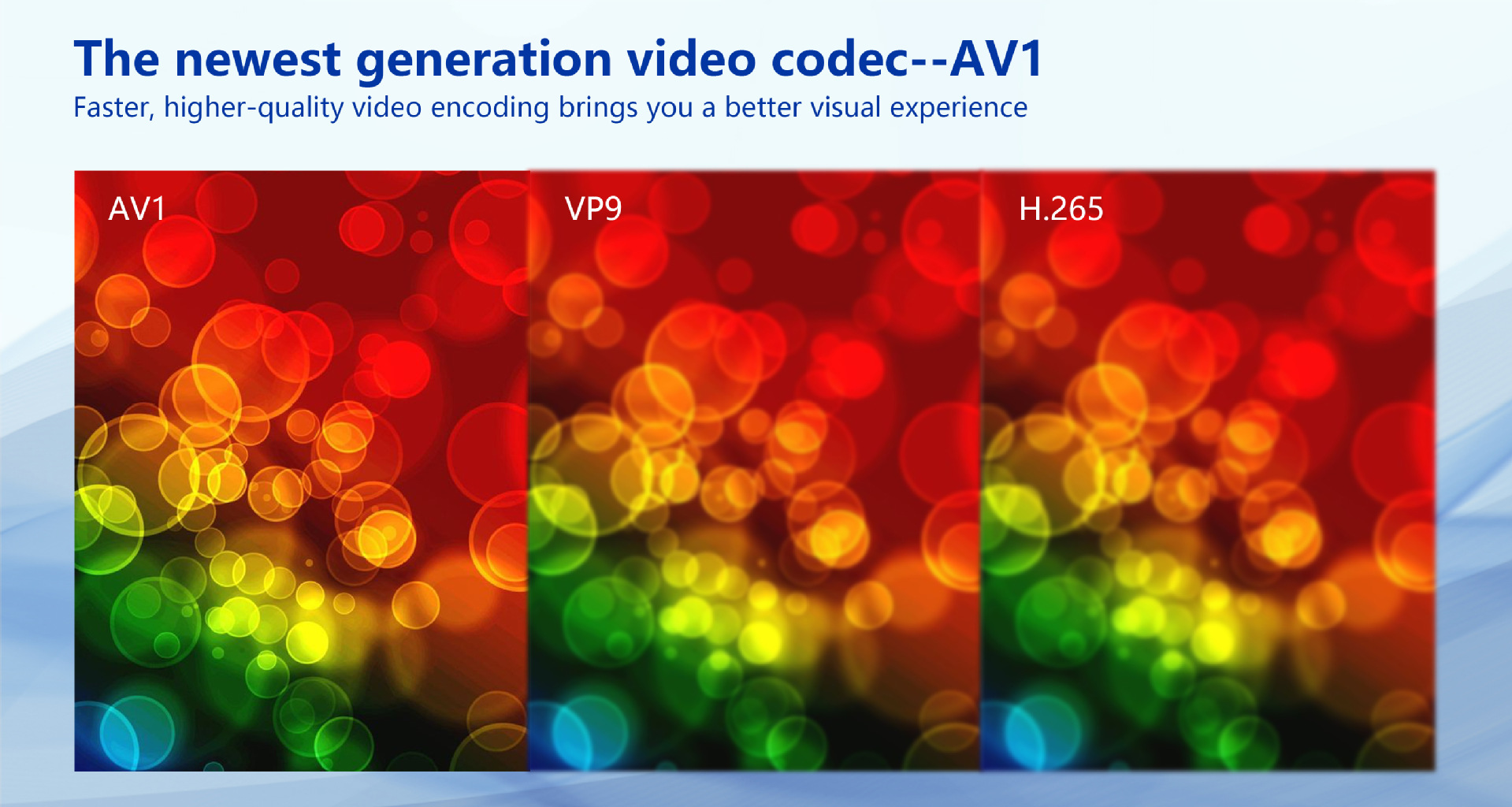

AV1: the next generation of video codecs

AV1 is touted to be the new video format for the Internet and is supposed to replace the well-known and proven MPEG format. AV1 codec is a performance-strong and license-free video codec and the brainchild of an alliance between Google’s VP10, Mozilla’s Daala and Cisco’s Thor.

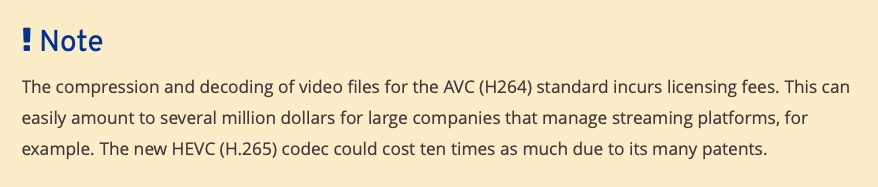

Over the last few years, MPEG codes including MPEG1, MPEG2, and MPEG4 variants ASP (DivX/XviD), AVC (H.264) and HEVC (H.265) were the measure of all things when it came to video streaming online. Streaming providers preferred HEVC for their 4K content. But MPEG formats have become the standard for highly compressed video files on DVDs, Blu-rays, and digital television as well.

The lack of competition for MPEG formats is not only due to their technological superiority. Many of the algorithms are patented, which has always made it difficult for third-party providers to launch a comparable codec. This affects commercial use of HEVC since streaming providers require a license from MPEG as well as other licensing partners, including individual patent holders. AV1 hopes to avoid these difficulties and, at the same time, provide a technically advanced solution over previous formats.

- What is AV1 codec?

- How does AV1 codec work?

- AV1 codec in comparison to other formats

- AV1 support

- How is AV1 codec being used?

What is AV1 codec?

AV1 is an open source video coding format designed to help businesses and individuals transmit high quality videos more efficiently online. Mozilla, Google, and Cisco are promoting the project to remove existing technological and financial barriers for users. The goal is for all users to gain access to powerful media formats and ultimately use them to exchange and playback video files on their open web platforms – such as the Firefox browser or YouTube.

The creators of AV1 codec joined forces as part of the Alliance for Open Media (AOMedia) which has been developing codecs, formats, and technologies for the open web since 2015. AOMedia Video 1 or AV1 in short is the first of its projects to be made available to the public. The open source, license-free AV1 codec is used to compress video files. Encoded files can be saved either as MP4 or MKV. Within WebM, AV1 can be used in conjunction with the audio format Opus to embed HTML5 videos.

Why is AV1 important?

According to research by Cisco, video content now accounts for 70 percent of Internet traffic. This number is expected to grow to over 80 percent by 2021. Even small improvements in file size, image quality, and transmission time make a big difference to creators and end users. AV1 is available free of charge and thus allows small companies and private individuals to enter the market who would otherwise not be able to afford the high license fees of other formats.

A brief history of AV1 codec

High licensing fees aren’t a new problem. Six years ago, nearly all the major players began work on their own viable alternatives to patented video codecs: Google published VP9, Mozilla launched its Daala project, and Cisco acquired Thor, a codec that is particularly suitable for low-complexity video conferences. Their goal was the same: to create the next generation video codec that would make sharing videos online faster, easier, and cheaper.

In 2015, they joined forces under AOMedia and streaming and hardware giants such as Amazon, Netflix, Intel, AMD,and NVIDIA jumped on board. The result is AV1 codec, which is primarily based on Google VP9, but benefits greatly from the tools and technologies provided by Daala, Thor, and VP10. Since 2018, Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox – two of the world’s most frequently used browsers – have supported AV1.

How does AV1 codec work?

AV1 is a media codec, i.e., a computer program that can encode or decode digital video, as well as photo and audio files. Encoding enables users to compress their files for efficient editing, storage, and sharing. The decoding then allows them to open or play the content – usually via an app or online player. For this interaction to work, the encoding and decoding process must be based on a shared format – in this case AV1.

It’s not quite as simple as it sounds. The interaction of media, application, and device hardware is a highly complex one, which requires codecs to be specialized. Today there are countless codecs in use, some of which are open source and free of charge, and some of which require a license and are subject to a fee.

AV1 as a new standard

AV1 will be standardized soon by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) under the name NetVC (Internet Video Codec). YouTube now supports AV1 codec and already offers 8K streams for compatible screens. This aim is to prove the efficiency of AOMedia’s AV1 codec compared to competing formats.

Beyond video

With AVIF, the Alliance for Open Media has also launched an image format based on the AV1 video codec. In the long term, the image format is likely to attract a comparably high demand and is aimed at replacing the JPEG format. The file extension is .avif (AV Image File); image sequences end in .avifs. The new image format is intended to achieve high image quality at higher compression rates and even supports animations as an alternative to the outdated GIF format.

AV1 codec in comparison to other formats

AOMedia’s AV1 differs from AVC in a few ways. AVC was launched in 2003 by the Moving Picture Experts Group (MPEG). The goal of AV1 is to become the dominant video format on the Internet. High-quality videos should be able to be exchanged freely and efficiently across the World Wide Web.

The biggest advantages of AV1 are:

- AV1 uses compression technology which is nearly twice as fast as competitors.

- Videos can be streamed in higher quality and faster.

- AV1 is license-free. There are no fees associated with the coding, decoding, and compression of video files.

- End users can enjoy a high-quality video even with lower Internet bandwidths.

AV1’s performance targets are ambitious. AOMedia plans to boost the efficiency by 25 percent compared to HEVC. When it comes to boosting complexity, software decoding is still the focus, because hardware support remains a long way off. AV1 is already usable in conjunction with the Opus audio format in WebMcontainer files in all common web browsers. The only exception is the Safari browser, which currently only supports Opus.

AV1 support

AV1 codec was initially suitable for use in Chrome and Firefox. This has since been followed by Microsoft’s and Apple’s native browsers. But the list of AV1 supporters doesn’t end there. Media content distributors such as Netflix, Amazon, Hulu, Apple,and Google are members of AOMedia alongside hardware providers such as Intel, AMD, ARM, and Nvidia. YouTube has been an early adopter of AV1 and has been testing the video format since 2017. The AV1 codec has been available for free use on Googlesource since 2018.

Hardware support

The following hardware products already support AV1:

- Allegro DVT launched a multi-format video encoding hardware that supports AV1.

- Samsung’s Q950TS TV supports 8K-streaming with AV1.

- LG’s ZX-OLED series can also stream in 8K thanks to AV1 support.

- Intel’s graphics processor Intel Xe launched an AV1 hardware decoder.

- Nvidia’s RTX 30 series supports 8K, 10bit and 60 fps thanks to AV1 codec.

- Amlogic S905X4 series and S905W2 series android TV box support AV1 codec.

Software support

The list of software that supports AV1 is much longer. Here are some well-known examples:

- Google Chrome

- Mozilla Firefox

- Microsoft Edge

- Opera

- Vivaldi

- Pale Moon

- VLC media player

- Android 10

How is AV1 codec being used?

AOMedia launched AV1 codec in June 2018. Since then, the bit stream has been stabilized and is available to any interested user on a license-free basis. The patent license is fully compliant with the W3C Patent Policy, which makes AV1 free to use. All browser manufacturers can use AV1 codec as an open web standard.

AV1 codec can already be used via Android TV with compatible devices. These include televisions with Broadcom’s BCM72190 and 72180 and Realtek RTD1311 or RTD1319.

Once 8K streaming becomes more established, AV1 is going to be used increasingly frequently.